Over the past century or two, the concept we’ve come to call “the silk road” has taken on a romantic haze which obscures truth. Here are some of the most popular myths, and some truths modern historians suggest instead.

Myth: They called it the silk road.

The truth: It’s a modern term, only applied in the 19th century. (It was largely popularized by a German geologist and explorer in 1877, but there’s evidence of its use earlier in the century as well.) But just because the weren’t booking passage on a trip called “The Silk Road” with travel agents doesn’t mean there weren’t numerable and regular trade routes across Afro-Eurasia which folks could rely upon.

Want to learn more?

A Traveler’s History of the Silk Road: Revelations from Dunhuang Materials, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8-ACQHbWiBg.

Jacobs, Justin M. “The Concept of the Silk Road in the 19th and 20th Centuries.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History, 2020. https://www.academia.edu/44620087/The_Concept_of_the_Silk_Road_in_the_19th_and_20th_Centuries.

Mertens, Matthias. “Did Richthofen Really Coin” the Silk Road”?” The Silk Road 17, no. 1 (2019): 1–9.

Waugh, Daniel. “Richthofens Silk Roads: Toward the Archaeology.” https://www.academia.edu/3157106/Richthofens_Silk_Roads_Toward_the_Archaeology.

Whitfield, Susan. “Was There a Silk Road?” Asian Medicine 3, no. 2 (2007): 201.

Myth: There was only one silk road.

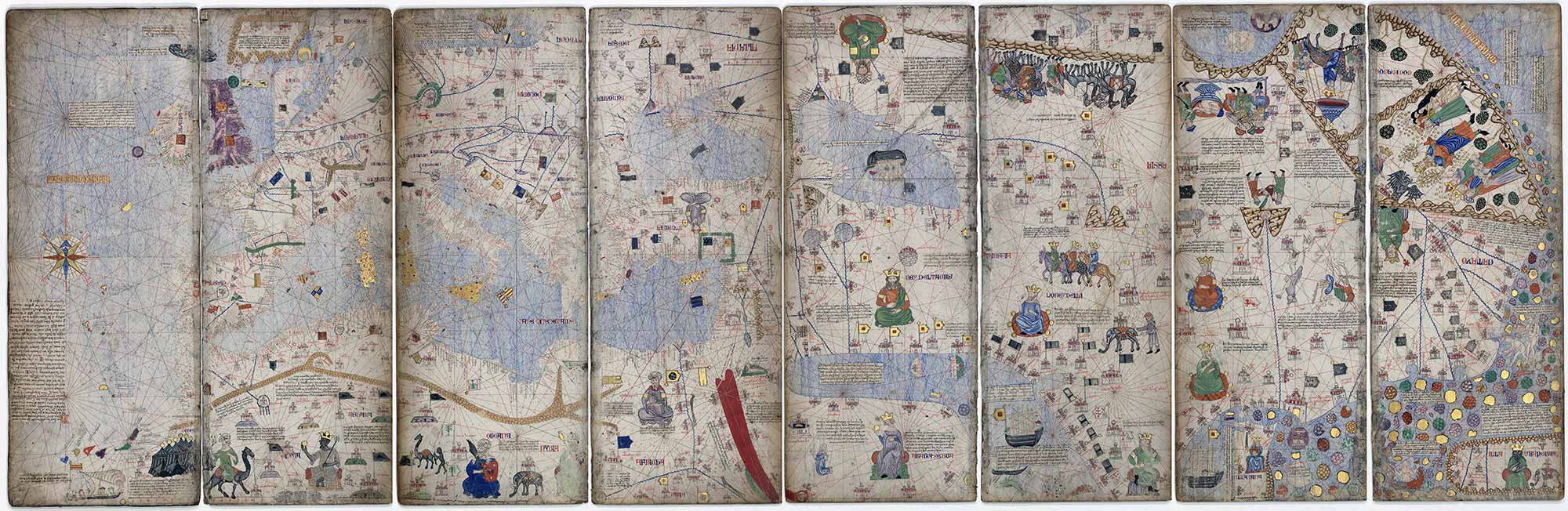

The truth: Historians have read many extant documents and traced physical evidence to build a picture of a web of trade which stretched across three continents. (Because of this, if necessary to refer to them, it’s closer to reality to call them the silk roads.)

Want to learn more?

“Map of the Silk Roads · Hidden Stories: Books Along the Silk Roads · Hidden Stories: Books Along the Silk Roads.” https://hiddenstories.library.utoronto.ca/exhibits/show/hidden-stories-books/the-silk-roads.

Silk Road Maps – Historical Map Collection and Satellite Images for Exploring Silk Road | Digital Silk Road. http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/geography/.

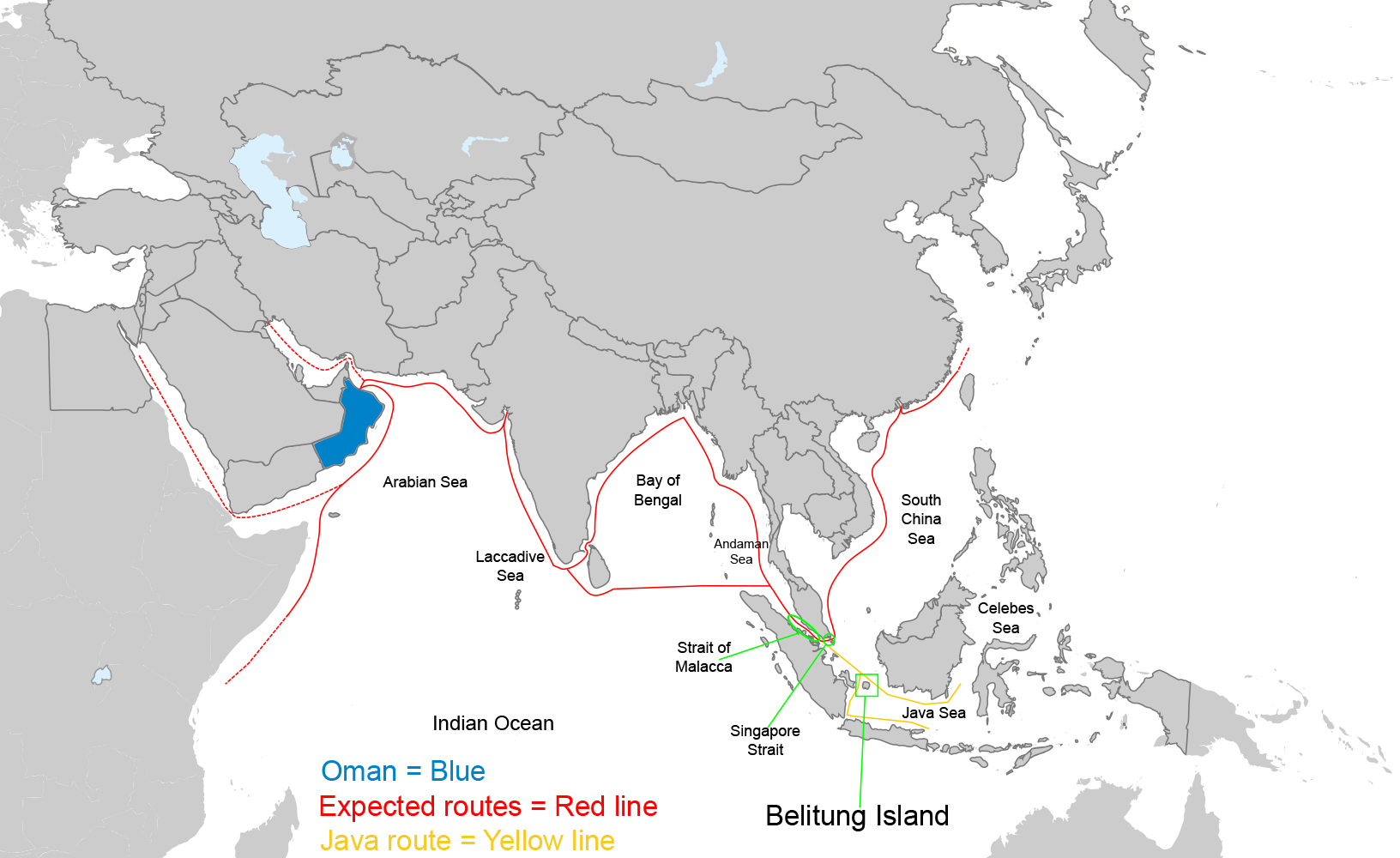

Myth: It was only a land route.

The truth: It was land and sea. As you can see below, we have a picture of thriving and reliable sea routes, often dictated by seasonal weather.

For example:

In the 9th century, an Arab ship running its regular trade route sank, and with it all of its cargo—cargo which gives us a perfect snapshot of trade at the time.

A large portion of this cargo included about 60,000 ceramic pieces of all shapes and sizes and kinds, and the story of these ceramics going between Iraq and China is a fascinating story of artistic conversation.

Want to learn more?

Heng, Geraldine. “An Ordinary Ship and Its Stories of Early Globalism: World Travel, Mass Production, and Art in the Global Middle Ages.” Journal of Medieval Worlds 1, no. 1 (March 1, 2019): 11–54. https://doi.org/10.1525/jmw.2019.100003.

“Tang Shipwreck.” https://www.nhb.gov.sg/acm/galleries/maritime-trade/tang-shipwreck

Mirza, Sana. “The Visual Resonances of a Harari Qur’ān: An 18th Century Ethiopian Manuscript and Its Indian Ocean Connections.” Afriques. Débats, Méthodes et Terrains d’histoire, no. 08 (December 28, 2017). https://doi.org/10.4000/afriques.2052.

Myth: It went only across Eurasia.

The truth: Since antiquity, Africa was known to be an integral (and, in some regions, very rich) cog in the massive, interlinked engine of trade across Afro-Eurasia. It was only when European colonization, imperialism, and the transatlantic slave trade began did it become “necessary” to excise most of Africa from the picture. Historians are finally beginning to weave it back in.

For example, the copper for the sitting figure on the right comes from a similar region to where the ivory madonna on the left was made, and the ivory for the madonna came from a Savannah elephant, indigenous to the region in Africa where the seated figure was made, indicating a mutually beneficial trade arrangement.

Want to read more?

“Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time: The Long Reach of the Sahara.” https://africa.si.edu/exhibitions/current-exhibitions/caravans-of-gold-fragments-in-time-art-culture-and-exchange-across-medieval-saharan-africa/long-reach/.

Guérin, Sarah M. “Exchange of Sacrifices: West Africa in the Medieval World of Goods,” 2017.

———. “Forgotten Routes? Italy, Ifrīqiya and the Trans-Saharan Ivory Trade.” Al-Masāq 25, no. 1 (2013): 70–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503110.2013.767012.

———. “Trans Saharan and Inter-Regional West African Trade 800-1500 CE” Bouctou | Center for African Studies, 1 (Fall 2022) 5–10. https://cfas.howard.edu/outreach/bouctou.

Desert Empires – History Of Africa with Zeinab Badawi [Episode 10], 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=shEU4PQUxxA.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara.” https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2020/sahel-art-empire-sahara.

Dowler, Amelia, and Elizabeth R. Galvin. “Money, Trade and Trade Routes in Pre-Islamic North Africa.” British Museum Research Publications, 2011. https://britishmuseum.iro.bl.uk/concern/books/af716cc1-05fe-4ba9-a686-bcdf2a102e6b?locale=en.

Myth: It went only east and west.

The truth: As described above, it went north, south, east, and west. The web of trade connected three continents, from Britain to Japan, from India up to Mongolia, Zimbabwe to Russia.

And nothing demonstrates the multidimensional spread of trade routes like the trade of textiles for horses.

While we mostly think of the camel when we think of the Silk Roads, the horse was equally if not more important. Horses were necessary for foreign relations, autonomy, intercommunication, military might, and for the recreational diplomacy of hunting and polo.

While we mostly think of the camel when we think of the Silk Roads, the horse was equally if not more important. Horses were necessary for foreign relations, autonomy, intercommunication, military might, and for the recreational diplomacy of hunting and polo.

But mostly due to the constraints of weather and geography, maintaining an adequate breeding population was difficult in many regions of the world. Therefore, they needed to be obtained from elsewhere—diplomatically, less-than diplomatically (war), or through trade.

The trade of textiles for horses is a commonality that weaves together regions for thousands of years; historian James Millward has called it “the warp and weft of the silk road”.

Want to read more?

Buell, Paul. “The Horse and the Silk Road: Movement and Ideas.” https://www.academia.edu/218892/The_Horse_and_the_Silk_Road_Movement_and_Ideas.

“Beyond Preaching: Papal Legate and Sino-Western Contact in Mongol-Yuan Eurasia, 1206–1368 – ProQuest.” https://www.proquest.com/openview/d1e1bd8ca2a23112f8b5113764ad2e34/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

“East Meets West under the Mongols.” http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/vol3num2/6_blair.php.

Elbl, Ivana. “The Horse in Fifteenth-Century Senegambia.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 24, no. 1 (1991): 85–110. https://doi.org/10.2307/220094.

Komaroff, Linda, Stefano Carboni, and N.Y.) Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York. The Legacy of Genghis Khan : Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353. New York, [New Haven]: Metropolitan Museum of Art ; [Distributed by Yale University Press], 2002.

Nam, Jong-Kuk. “The Envoy to Pope Benedict XII by the Great Khan in 1336,” http://medsociety.or.kr/down/2019/2019-9-Jong-Kuk%20NAM.pdf.

Myth: It was only about connecting Europe and China. (Do not pass go, do not collect $200.)

The truth: It was just as much about all the stops and people in between. Without all the connection points, not only would goods be unable to get from place to place, but there wouldn’t have been as many goods.

meet the Sogdians

The Sogdians were primarily a merchant society (merchants, craftspeople, entertainers) who traveled primarily across Central and East Asia. At their height from around the 4th–8th centuries CE, they were the trading engine of The Silk Roads.

Besides the Sogdians and the Khotanese—both civilizations fundamentally necessary to intra-regional Eurasian trade, who enabled and encouraged movement of trade and people—the tough geography of Central Asia also required rest stops with resources and knowledge if travellers were to succeed. The Dunhuang oasis is one such location.

the Dunhuang oasis

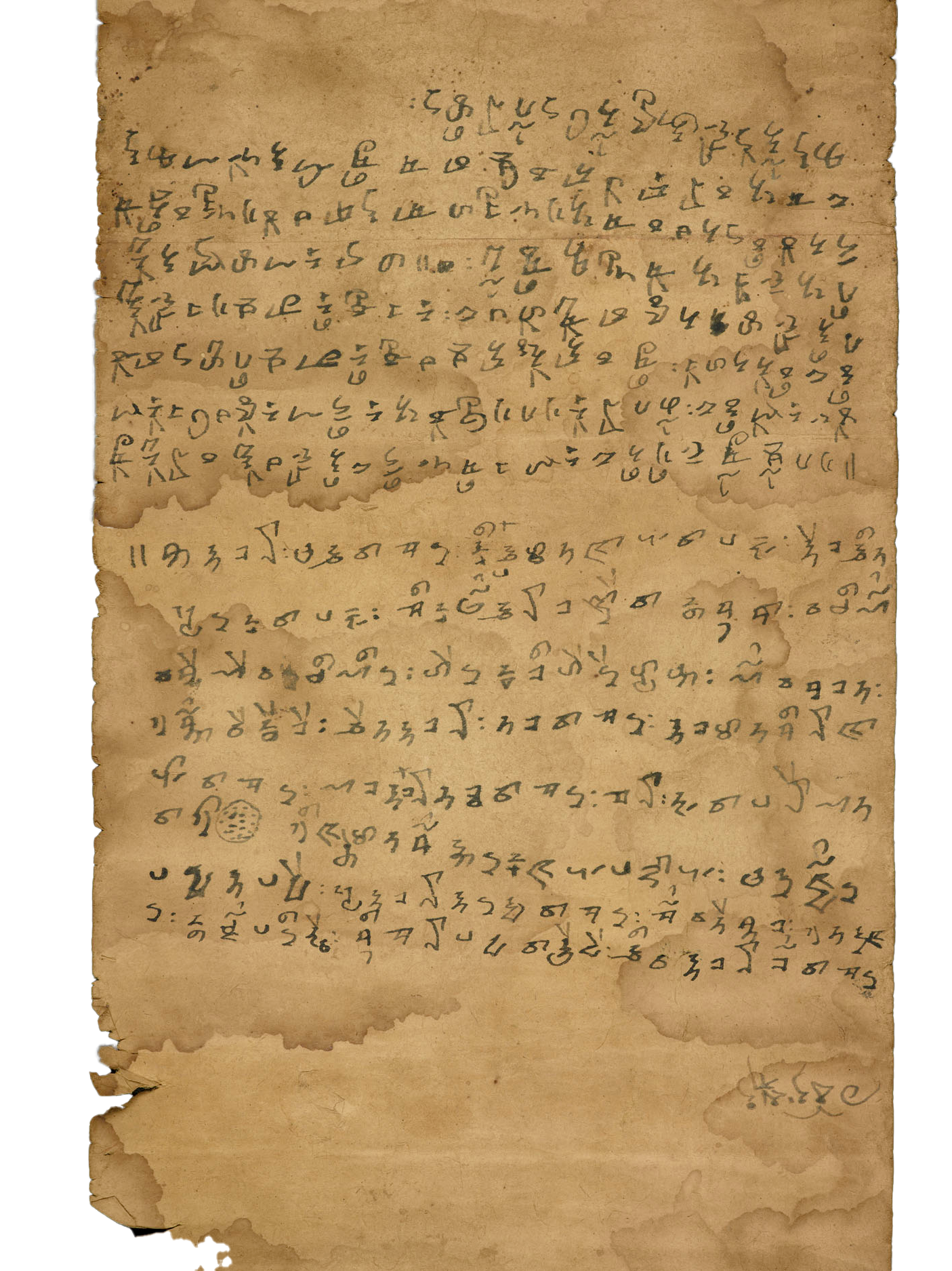

In the early 20th century, a cave was found in Dunhuang containing several thousand texts in many languages, all pertaining to various sorts of topics related to Silk Road trade, excepting actual trade itself. They talked about logistics, communications, advice for travellers, and more, including this phrase sheet translating between Chinese and Khotanese, not unlike the ones modern travellers access on their smartphones today.

Paper, its spread and its use, is possibly the most important consequence of the Silk Road trade routes.

Want to read more?

“The Sogdians.” https://sogdians.si.edu/.

Skaff, Jonathan Karam. “The Sogdian Trade Diaspora in East Turkestan during the Seventh and Eighth Centuries.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 46, no. 4 (2003): 475–524.

Sims-Williams, Nicholas. “The Sogdian Fragments of the British Library.” Indo-Iranian Journal 18, no. 1/2 (1976): 43–82.

“Badamu Document: Mediators between Chinese and Turkish Tribes” https://kimon.hosting.nyu.edu/sogdians/items/show/942.

SAL Evening Lecture: Khotan: A Neglected Silk Road Kingdom, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lw4v97Ir6GI.

“Silk Road or Paper Road?” http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/vol3num2/5_bloom.php

A Traveler’s History of the Silk Road: Revelations from Dunhuang Materials, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8-ACQHbWiBg.

Bloom, J.M. Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World. ACLS Humanities E-Book. Yale University Press, 2001.

“Hidden Treasures of the Silk Road. Aurel Stein and the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas.” http://dunhuang.mtak.hu/index-en.html.

Kralka, Paulina. “Conserving Paper: Reflections on Cultures of Conservation in Europe and East Asia.” Journal of the Institute of Conservation 45, no. 2 (May 4, 2022): 135–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/19455224.2022.2068634.

Myth: It was only about silk.

The truth: The legacy of historical trade is about so much more than silk, so much more than commerce, so much more than goods. Trade allowed religions, technological innovations, and culture to spread, so our world would be incalculably different if this long- and short-distance trade hadn’t happened.

religion

An essential Buddhist text about the tenet of nonindividuality, the Diamond Sutra is our earliest extant printed book. Block printed in China in 868, and thereafter making its way to the cave library at Dunhuang, its a perfect representation of the way paper allowed religion to spread. In addition, missionaries carrying paper and religion could more easily travel alongside experienced merchants than they could have on their own.

music

Many of the plucked and bowed string instruments of Asian and European modern ensembles were developed and spread by horse-riding folk of the steppe. In fact, any number of bowl-bodied, four-stringed instruments like the pipa, the lute, the oud, and the barbat share a common lineage.

food

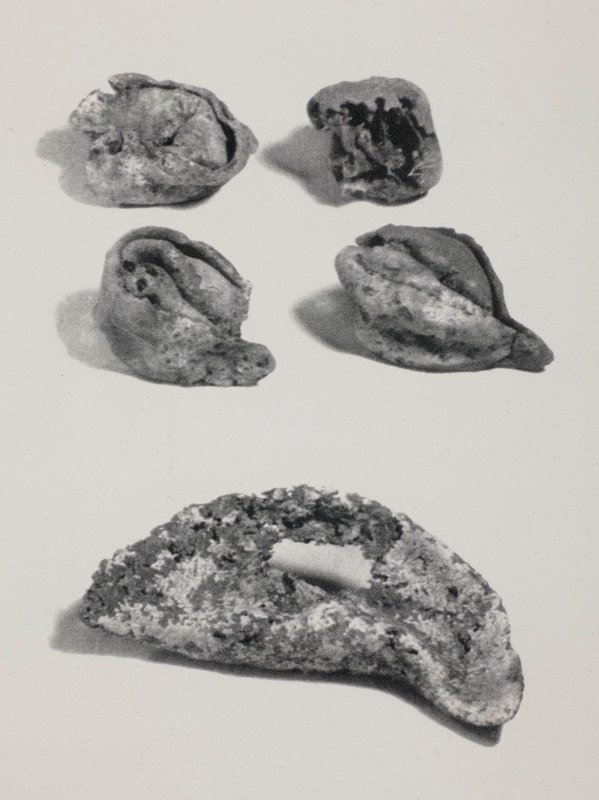

Wine grapes, citrus, sugar cane, eggplant, buckwheat, rice, peaches, alfafa, watermelon, and more traveled the trade routes alongside other goods and culture. The dry conditions at the oases of Turfan preserved many perishable items, like these two wontons and a dumpling at left, giving us an opportunity to see intimate details of food culture. This specific form of dumpling traveled along the silk routes, demonstrated by its existence in traditional cuisine as well as the linguistics of their names.

stories

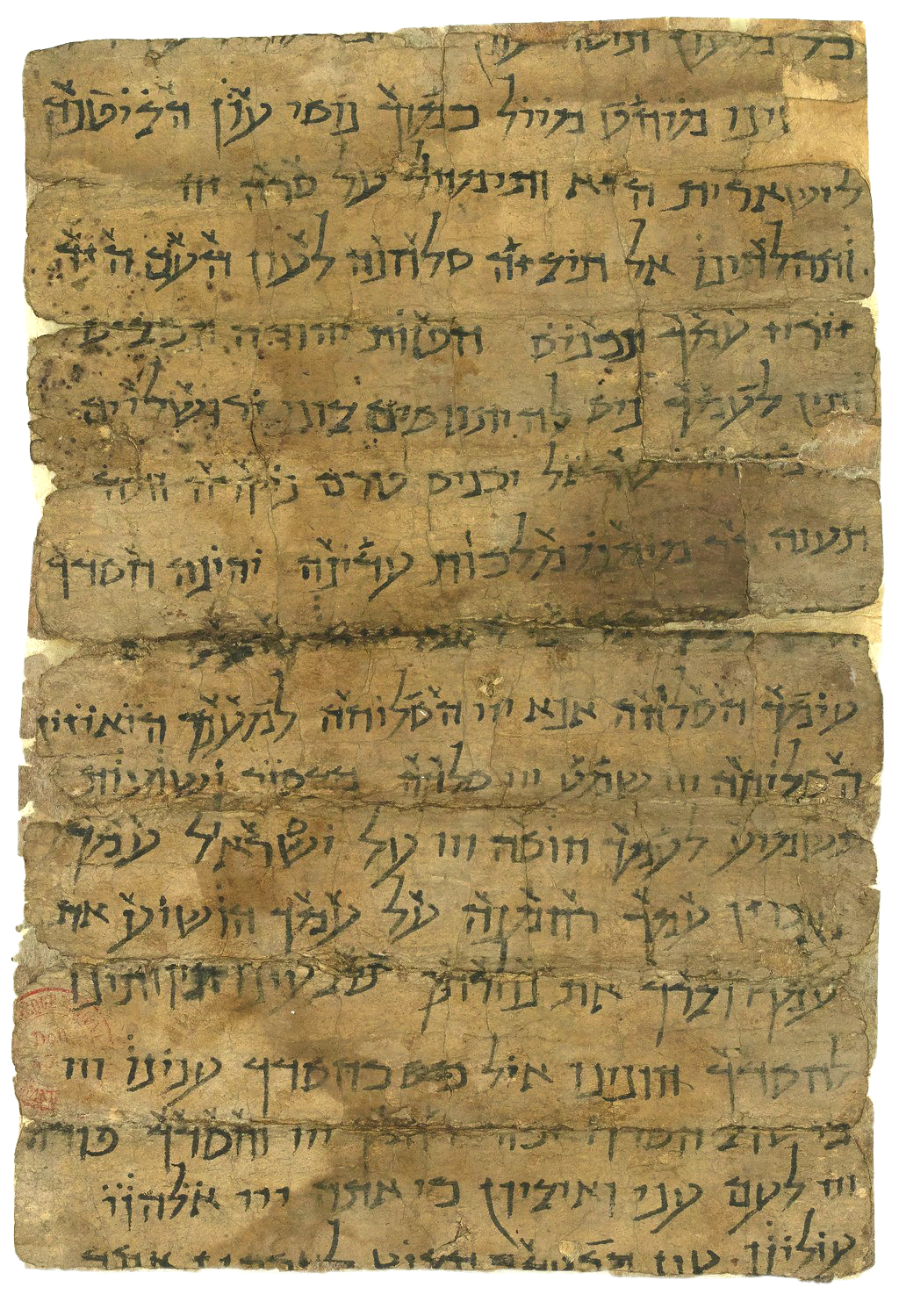

The silk roads flowed with stories. One such shared tale is the Alexender Romance, originally written in the 3rd century Greece and spreading throughout Afro-Eurasia.

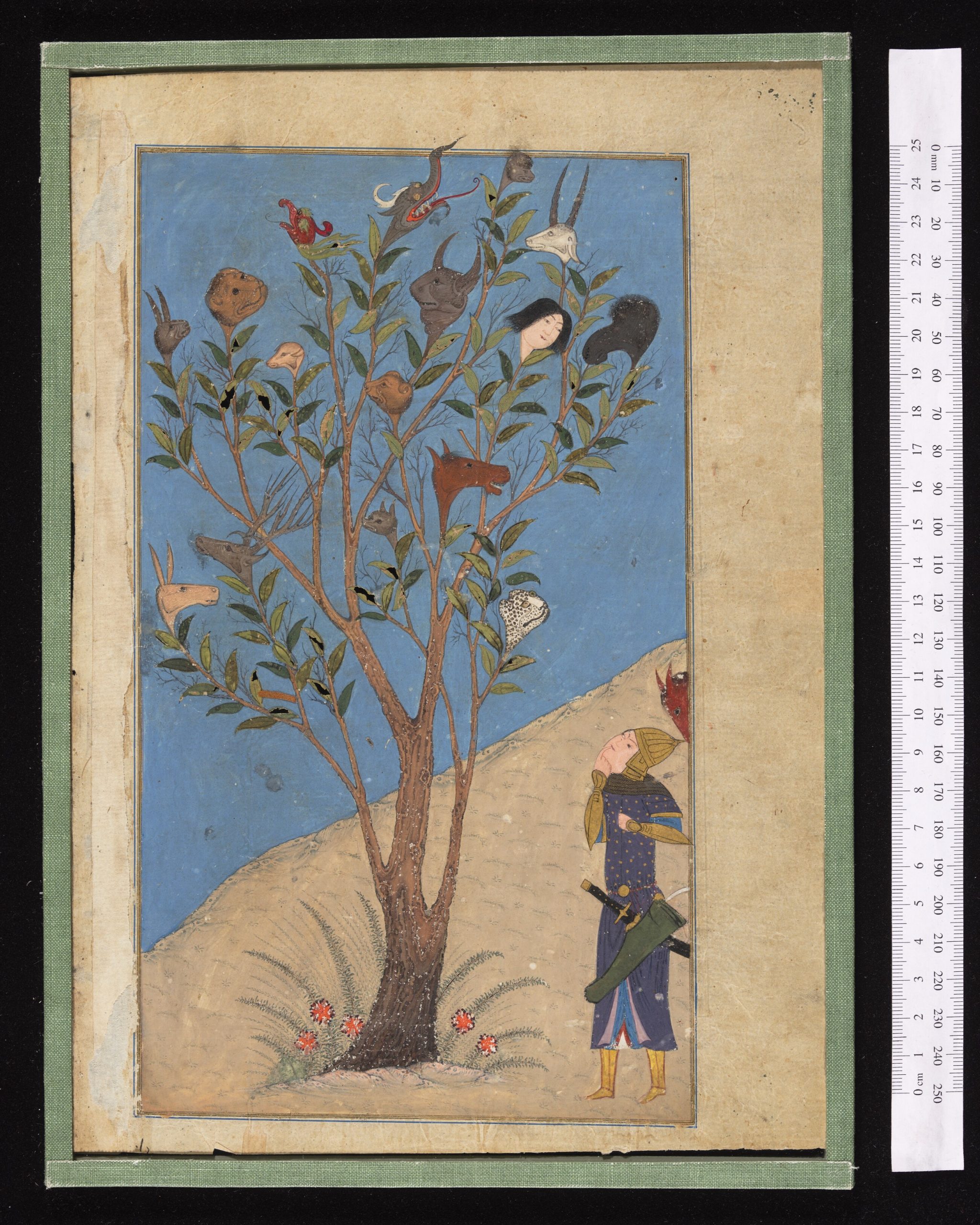

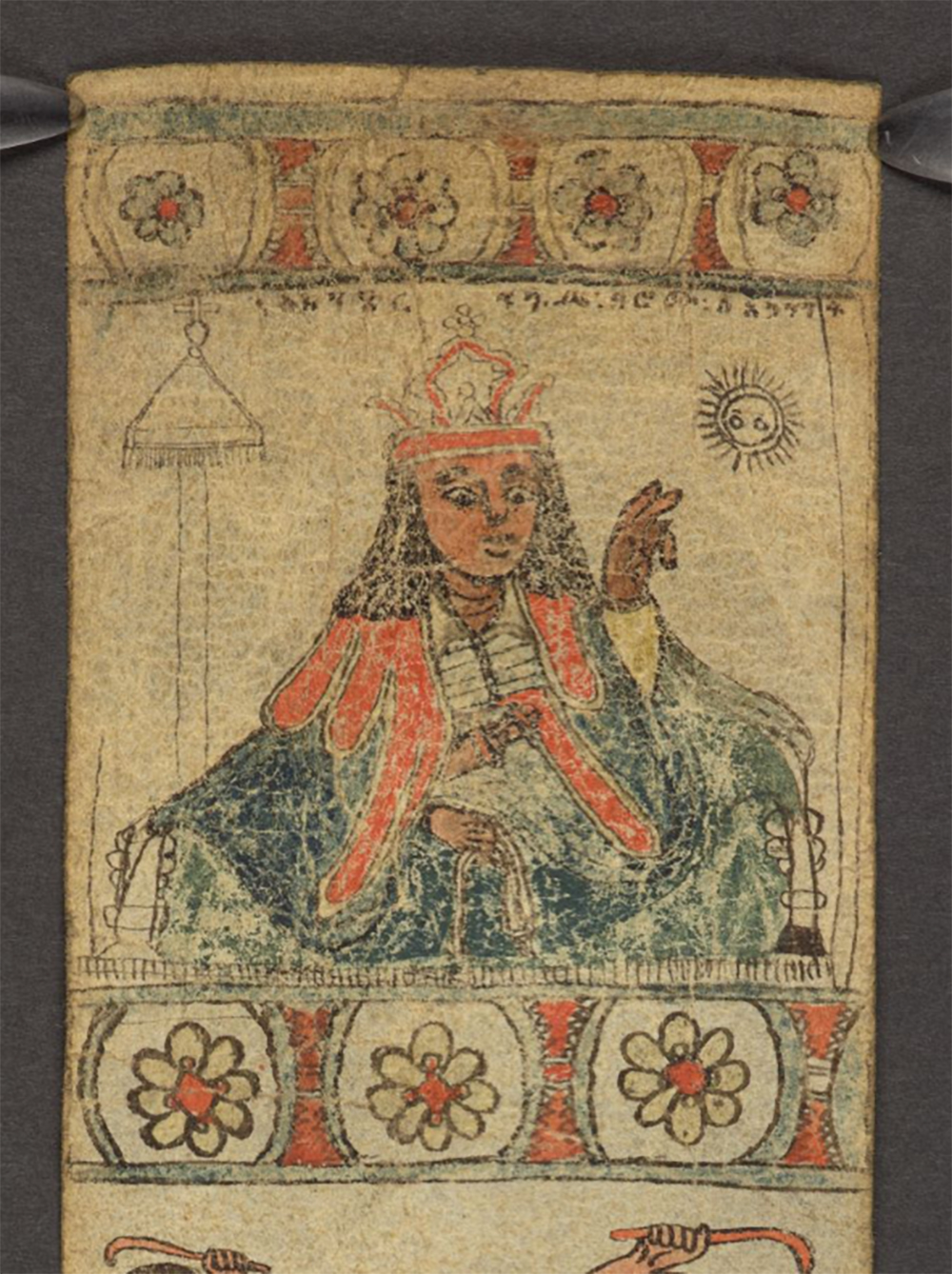

The three manuscripts below are connected by the way in which they transform the tale of Alexander to suit the culture and location in which they were made. At center, the English tale depicts the story of Alexander with a soothsayer at the trees of the Sun and Moon, getting a prophecy. At left, Alexander is getting his prophecy from a Waqwaq tree, a traditional element in Persian storytelling. And at right, Alexander takes the place of high strength and protective ability within an Ethiopian amulet scroll. In the Ethiopian tale of Alexander, the exotic queen Candace is relocated from Ethiopia (which, after all, would not have seemed exotic to Ethiopians) to Babylon.

The variations of this story as it travels from culture to culture illustrate our similarities, our differences, and how we are all at the center of our own worlds.

Want to read more?

Susan Whitfield on the Diamond Sutra, 2015. https://soundcloud.com/the-british-library/susan-whitfield-on-the-diamond.

Kishibe, Shigeo. “The Origin of the P’i P’a: With Particular Reference to the FiveStringed P’i P’a Preserved in the Shôsôin.” Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan 19 (1940): 259–304. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015046337088&view=1up&seq=292&q1=Kishibe.

Millward, James A. “From Camelback to Carnegie Hall: The Global Journey and Modern Makeover of the Pipa.” https://www.academia.edu/33126642/From_Camelback_to_Carnegie_Hall_the_Global_Journey_and_Modern_Makeover_of_the_Pipa.

Hu, Jun. “Global Medieval at the ‘End of the Silk Road,’ circa 756 CE: The ShōSō-in Collection in Japan.” The Medieval Globe 3, no. 2 (2017): 177–202.

“Lunchtime Lecture: Tombs, Temples, and Sacred Sites: Testing the Limits with Alexander the Great” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kEorBf6twss.

“Alexander the Great: A Life in Pictures.” https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2023/02/alexander-the-great-a-life-in-pictures.html.

“Alexander the Great in Firdawsi’s Book of Kings.” https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2022/10/alexander-the-great-in-firdawsis-book-of-kings.html.

Casagrande-Kim, Roberta, Samuel Thrope, Raquel Ukeles, and New York University. Romance and Reason : Islamic Transformations of the Classical Past. New York, NY: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University, 2018.

Hillenbrand, Robert. “The Iskandar Cycle in the Great Mongol Shahnama”. The Problematics of Power: Eastern and Western Representations of Alexander the Great. Eds. M.Bridges and J.Ch.Bürgel (Bern, 1996), 203-30. https://www.academia.edu/33180698/

Hillenbrand, Robert. “‘The Shahnama and the Persian Illustrated Book’, in Literary Cultures and the Material Book, Eds. S.Eliot, A.Nash and I.Willison (London, 2007), 95-119.” https://www.academia.edu/32937964/_The_Shahnama_and_the_Persian_Illustrated_Book_in_Literary_Cultures_and_the_Material_Book_eds_S_Eliot_A_Nash_and_I_Willison_London_2007_95_119.

MAP Academy. “The Waq-Waq Tree and How It Fuelled the Mughal Imagination,” November 26, 2021. https://mapacademy.io/the-waq-waq-tree-and-how-it-fuelled-the-mughal-imagination/.

Sirén, Osvald. “Central Asian Influences in Chinese Painting of the T’ang Period.” Arts Asiatiques 3, no. 1 (1956): 3–21.

Sheikh, Samina. “Chinese Influence in Persian Manuscript Illustrations,” July 1, 2017.

Myth: It only existed in the Middle Ages.

The truth: Historians of the silk routes generally began detailing its trade a few centuries BCE and stop sometime in the early modern period, but this timeframe is almost arbitrary. Interregional trade went back much further, and the trade of textiles for horses continues up to the current day. But this is the framework historians generally stick to.

In short, study of the Silk Roads is a useful place to start when approaching the study of premodern communication, exchange, and connectedness.

Want to read more?

Keene, Bryan C. and J. Paul Getty Museum. Toward a Global Middle Ages : Encountering the World through Illuminated Manuscripts. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019.

“Hidden Stories: Books Along the Silk Roads.” https://hiddenstories.library.utoronto.ca/exhibits/show/hidden-stories-books/welcome.

MIllward, James A. The Silk Road: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Perry, David, and Geraldine Heng. Whose Middle Ages? 1st ed. Fordham University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvnwbxk3.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. First edition. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Sims-Williams, Ursula. “The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith.” Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series 1 (2001): 163–70.

Heng Geraldine. Teaching the Global Middle Ages. Modern Language Association of America 2022.