An intro to Ethiopian Art through the 16th century, to set you on a path for your own research.

an important note

When viewing Ethiopian art, it might be helpful to keep in mind the existence of alternative objectives.

In her 1998 paper on Fre Seyon, Marilyn Heldman says:

"The pictorial illusionism of the Greco-Roman classical tradition, with its modeled forms and picture frame that simulates a window looking out into space, is essentially an artificial construct. It was carefully cultivated for ideological reasons at various times and places. … There was no reason to cultivate the classical Greco-Roman tradition in the art of the Ethiopian Church."

In those times and places the political ideal was Ancient Rome, and everything hearkened back to that classical heritage. But for Ethiopia, the ideal was the ancient Jerusalem of David and Solomon and of the emperor Constantine.

In our culture we have inherited those same political ideals which elevate classical Greek and Rome, and so have been trained (both subtly and overtly) to view art through a lens ground by those who heralded their art as the pinnicle. But it’s important to keep in mind that other intentions exist, and are both valid and beautiful.

Art has plenty of room for plurality.

a few KEY TERMS

- Geʽez or Gəʽəz: A script and a language.

The language of pre-16th century Eritrea and Ethiopia, extinct as an everyday language, but with continuing use in several Ethiopian and Eritrean liturgical settings. Its script (of the same name) is not only used to write the modern languages of Amharic and Tigrinya, but has been adapted to write other languages as well. - tholos/tempietto (Greek and Latin, respectively.)

Small temple. A motif in Gospel books, generally those stemming from the Greek tradition. Particularly important in Ethiopian manuscripts. - ḥaräg

The Gəʽəz word for the tendril of a climbing plant. Used to refer to the decorative headpieces of manuscript pages, particularly those of the 14th and 15th centuries. - sensul

A folded, accordion-style manuscript. A particularly Ethiopian form. - se’el

The Gəʽəz word for all images, whether 2D or 3D.

click for resources on Ethiopia and Ethiopian art, broadly

Albin, Andrew, Mary Carpenter Erler, Thomas O’Donnell, Nicholas Paul, and Nina Rowe. Whose Middle Ages? : Teachable Moments for an Ill-Used Past. First edition. Fordham Series in Medieval Studies. New York: Fordham University Press New York, 2019.

Babu, Blessen George. “Cultural Contacts between Ethiopia and Syria: The Nine Saints of the Ethiopian Tradition and Their Possible Syrian Background.” In Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity in a Global Context, 42–61. Brill, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004505254_005.

Bosc-Tiessé, Claire. “Christian Visual Culture in Medieval Ethiopia: Overview, Trends and Issues.” In A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, 322–64. Brill, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004419582_013.

Chojnacki, Stanislaw. “Short Introduction to Ethiopian Traditional Painting.” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 2, no. 2 (1964): 1–11.

“Christian Ethiopian Art.” https://smarthistory.org/christian-ethiopian-art/.

Derillo, Eyob. “Exhibiting the Maqdala Manuscripts: African Scribes: Manuscript Culture of Ethiopia.” African Research & Documentation 135 (January 1, 2019): 102.

Dixon, Sonia. “The Question of Authenticity: Two Ethiopian Icons.” Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 8, 1 (2022): 150-164. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol8/iss1/10.

“The Ethiopian Heritage Fund Charity.” http://www.ethiopianheritagefund.org

Heldman, Marilyn Eiseman. African Zion : The Sacred Art of Ethiopia. New Haven ; London : Yale University Press, 1993. http://archive.org/details/africanzionsacre1993held.

Heldman, Marilyn E. “The Sacred Art of Ethiopia.” The Historian 57, no. 1 (1994): 35–42.

The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection. “Traversing the Globe through Illuminated Manuscripts (The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection).” https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/exhibition/103PZC.

Keene, Bryan C. and J. Paul Getty Museum. Toward a Global Middle Ages : Encountering the World through Illuminated Manuscripts. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum Los Angeles, 2019.

Magazine, Minerva. “Saving Tigray’s Painted Churches | The Past,” February 18, 2021. https://the-past.com/feature/saving-tigrays-painted-churches/.

Magazine, Smithsonian, and David M. Perry Gabriele Matthew. “A New History Changes the Balance of Power Between Ethiopia and Medieval Europe.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/new-history-changes-balance-power-between-ethiopia-and-medieval-europe-180978084/.

“Mazgaba Se’elet: Treasury of Ethiopian Images | Digital Humanities Network.” https://dhn.utoronto.ca/project/mazgaba-seelet-treasury-of-ethiopian-images/.

Medieval Ethiopian Manuscript Collections in the British Library – Eyob Derillo, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n5uvoqJ7Y5A.

Ross, Emma George. “African Christianity in Ethiopia.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/acet/hd_acet.htm (October 2002)

UCL. “5. Baharä Maryam.” History of Art, March 15, 2023. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/art-history/research/demarginalizing-medieval-africa/exhibition-art-and-faith/5-bahara-maryam.

UCL. “Exhibition: Christian Art and Faith in the Ethiopian Empire, UCL Cloisters (September–October 2022).” History of Art, August 18, 2022. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/art-history/research/demarginalizing-medieval-africa/exhibition-christian-art-and-faith-ethiopian-empire-ucl.

Unesco et al. Ethiopia : Illuminated Manuscripts. New York Graphic Society : Paris : By Arrangement with UNESCO 1961.

Vansina, J. Art History in Africa: An Introduction to Method. Routledge, 2014.

Zewde, Bahru. “A Century of Ethiopian Historiography.” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 33, no. 2 (2000): 1–26.

KINGDOM of AKSUM (c. 4th-8th centuries CE)

Aksum was a city and kingdom in northern Ethiopia and Eritrea. A major naval and trading power from about the 1st–7nd centuries CE, most of what we know about it was written by other people. They describe it as one of the four greatest powers in the world, holding sway from the inner Arabian desert, across the Red Sea, to the west to parts of the Sahara.

As an important locus of trade, the kingdom began minting coins in about 270 CE. Not only are these coins evidence of this trade, but not too long thereafter they were also witnesses of the transition to Christianity; converting in the fourth century, Aksum was one of the earliest regions to do so—if not the first.

See below left, a coin with a bust of King Endubis with a disc and crescent in the border above his head. Only a few years later, the coin at right with King Ezanas—who converted the kingdom to Christianity—shows a cross in the same place.

Into this context enter the Garima Gospels.

Rather than one single manuscript, the Garima Gospels are grouping of gospel books, the earliest of which dates from 330–650 CE. (They were radiocarbon tested in 2013.) They contain the earliest intact grouping of all four evangelists and canon tables, as well as the earliest set of compete canon tables based on Greek prototypes. They are also the only extant manuscripts from this time period.

They contain a series of pages types which provide evidence of structural continuity with the earliest days of the church: Eusebius’s letter to Carpianus, the decorated canon tables, and the tholos (in Greek, tiempetto in Latin, both meaning “little temple”), which might have represented the harmony of the four gospels in the same way that separate columns are united under a single roof.

To the left, the tholos from the Garima Gospels I. To the right, an Armenian gospel book of the 10th century. Their shared lineage (both are based on early Greek models) is clear.

Some later Ethiopian manuscripts continue with a further program of images, about which more later. Whatever page types remain, from the 4th century until the 16th, all Ethiopian gospel books appear to be derived from the same early models.

click for resources on Aksum and the Garima Gospels

Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. “Foundations of Aksumite Civilization and Its Christian Legacy (1st–8th Century).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/aksu_1/hd_aksu_1.htm (October 2000)

The Garima Gospels I at VHMML https://www.vhmml.org/readingRoom/view/132896

The Garima Gospels II at VHMML https://www.vhmml.org/readingRoom/view/132897

Gnisci, Jacopo. “An Ethiopian Miniature of the Tempietto in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Its Relatives and Symbolism”. Canones: The Art of Harmony: The Canon Tables of the Four Gospels, edited by Alessandro Bausi, Bruno Reudenbach and Hanna Wimmer, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2020, pp. 67-98. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110625844-005.

Haas, Christopher. “Mountain Constantines: The Christianization of Aksum and Iberia.” Journal of Late Antiquity 1, no. 1 (2008): 101–26. https://doi.org/10.1353/jla.0.0010.

Kim, Sergey. “New Studies of the Structure and the Texts of Abba Garima Ethiopian Gospels.” Afriques. Débats, Méthodes et Terrains d’histoire, no. 13 (November 8, 2022). https://doi.org/10.4000/afriques.3494.

Merrills, A. H. (Andrew H.). “Monks, Monsters, and Barbarians: Re-Defining the African Periphery in Late Antiquity.” Journal of Early Christian Studies 12, no. 2 (2004): 217–44. https://doi.org/10.1353/earl.2004.0025.

McKenzie, Judith S., and Francis Watson. The Garima Gospels: Early Illuminated Gospel Books from Ethiopia. Manar Al-Athar, 2016.

Piovanelli, Pierluigi. (2019). Aksum and the Bible: Old Assumptions and New Perspectives. Aethiopica. 21. 10.15460/aethiopica.21.0.1161.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342954524_Aksum_and_the_Bible_Old_Assumptions_and_New_Perspectives.

The Rise Of Aksum – History Of Africa With Zeinab Badawi [Episode 5], 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A4OSEpexs_Q.

POST-AKSUMITE (c. 8th/9th–12th centuries CE)

Several circumstances, including Arab expansion into the north of Africa and spread of Islam, give us a historical lacuna in this period. The political center of Ethiopia seems to have shifted away from Aksum to Tigray. Rock-hewn building (more below) had long been a tradition even pre-Aksum, and may have continued to be made throughout, but subsequent stoneworking makes that hard to confirm.

ZAGWE (c. 1140–1270 CE)

No illuminated manuscripts or icons from the Zagwe time period have been discovered so far; scholars suggest this is due to systematic distruction when Yekunno Amlak established the so-called Solomonic dynasty in 1270, in an attempt to control the narrative.

But this doesn’t signify a lack of art.

Ge’ez uses the same word for all images, whether 2D or 3D—se’el—which is one reason why the Iconoclastic controversy in Byzantium never took hold. The art carved into or painted on the walls within rock-hewn churches can provide for us a throughline between the Kingdom of Aksum and the Solomonic dynasty of the 13th century.

The complex of Lalibela is notable for its 11 rock-hewn (carved from living rock) churches. Take a 3D tour though the structures at the link below.

click for more information on Lalibela

3D model of Beta Giorgis Church

Abullif, Wadi Awad, Emmanuel Fritsch, Claire Bosc-Tiessé, and Marie-Laure Derat. “Les Inscriptions Arabes, Coptes et Guèzes Des Églises de Lālibalā.” Annales D’Ethiopie 25, no. 1 (2010): 43.

Bosc-Tiessé, Claire, Marie-Laure Derat, Laurent Bruxelles, François-Xavier Fauvelle, Yves Gleize, and Romain Mensan. “The Lalibela Rock Hewn Site and Its Landscape (Ethiopia): An Archaeological Analysis.” Journal of African Archaeology 12, no. 2 (2014): 141–64.

Derat, Marie-Laure. “The Zāgwē Dynasty (11-13th Centuries) and King Yemreḥanna Krestos.” Annales d’Éthiopie 25 (2010), 157-196 https://www.academia.edu/37587456/The_Z%C4%81gw%C4%93_dynasty_11_13_th_centuries_and_King_Yemre%E1%B8%A5anna_Krestos.

Klyuev, Sergey. “The Rock-Hewn Churches of the Garalta Monasteries (Tigray, Ethiopia): The Comparative Analysis of Three Monuments of the Second Half of the 13th to the First Half of the 15th Centuries,” 117–22. Atlantis Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2991/ahti-19.2019.24.

Phillipson, David W. “Jerusalem and the Ethiopian Church: The Evidence of Roha (Lalibela).” In Tomb and Temple: Re-Imagining the Sacred Buildings of Jerusalem, edited by Eric C. Fernie and Robin Griffith-Jones, 255–66. Boydell Studies in Medieval Art and Architecture. Boydell & Brewer, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781787442115.018.

Windmuller-Luna, Kristen. “The Rock-hewn Churches of Lalibela.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/lali/hd_lali.htm (September 2014)

EARLY SOLOMONIC (1270-1527)

13th century

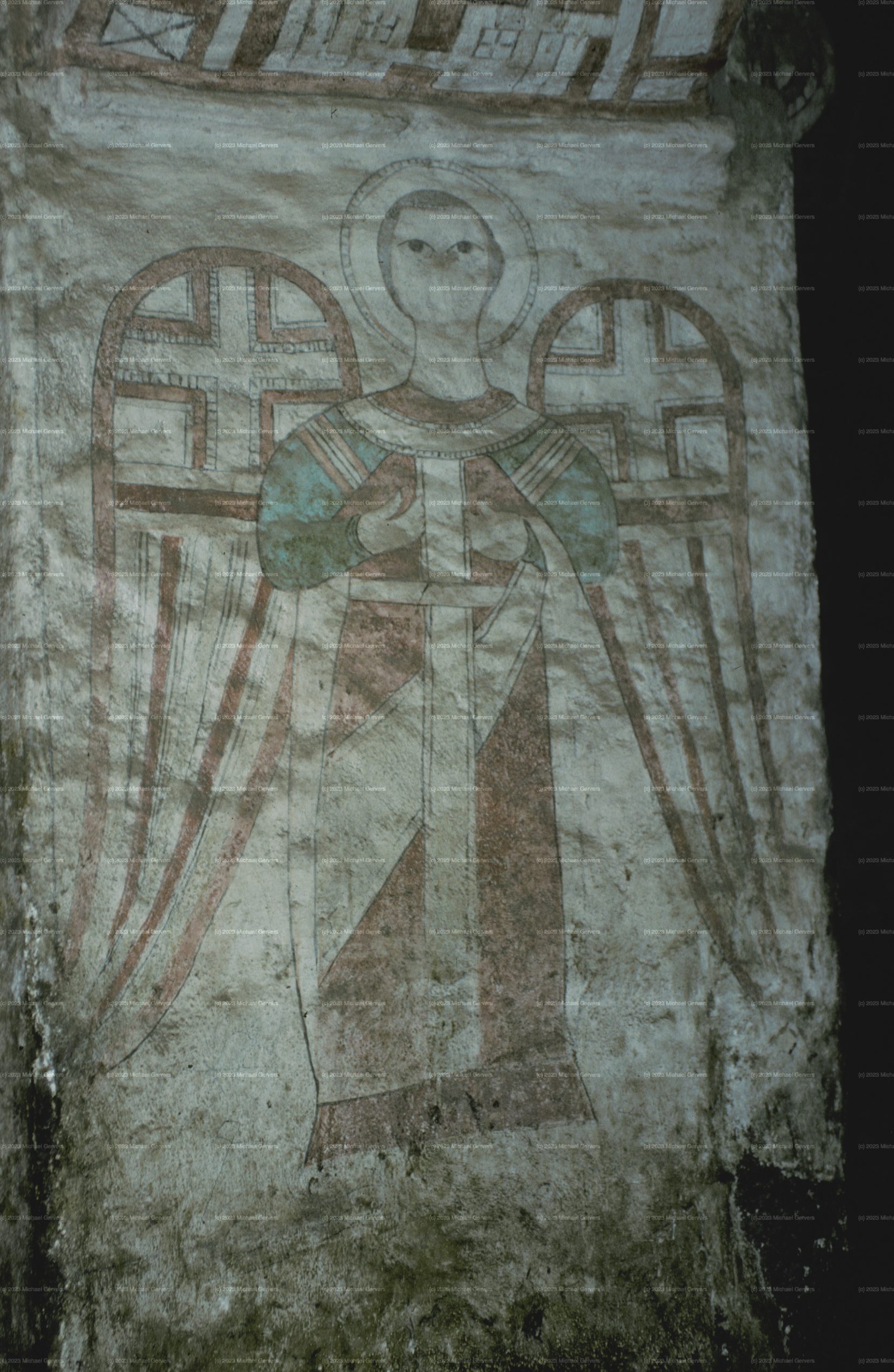

Churches such as those at Lalibela and Dabra Tsion feature artwork dated to this era, both figural and abstract. In the slides below, you can see only a tiny fraction of the photographs taken of this artwork and put up into Mäzgäbä Səəlat, a database created by leading scholars and continually updated.

13th–14th century

GOSPEL BOOKS

It’s at this point where we begin to have sufficient extant manuscripts that we can to draw even more structural connections.

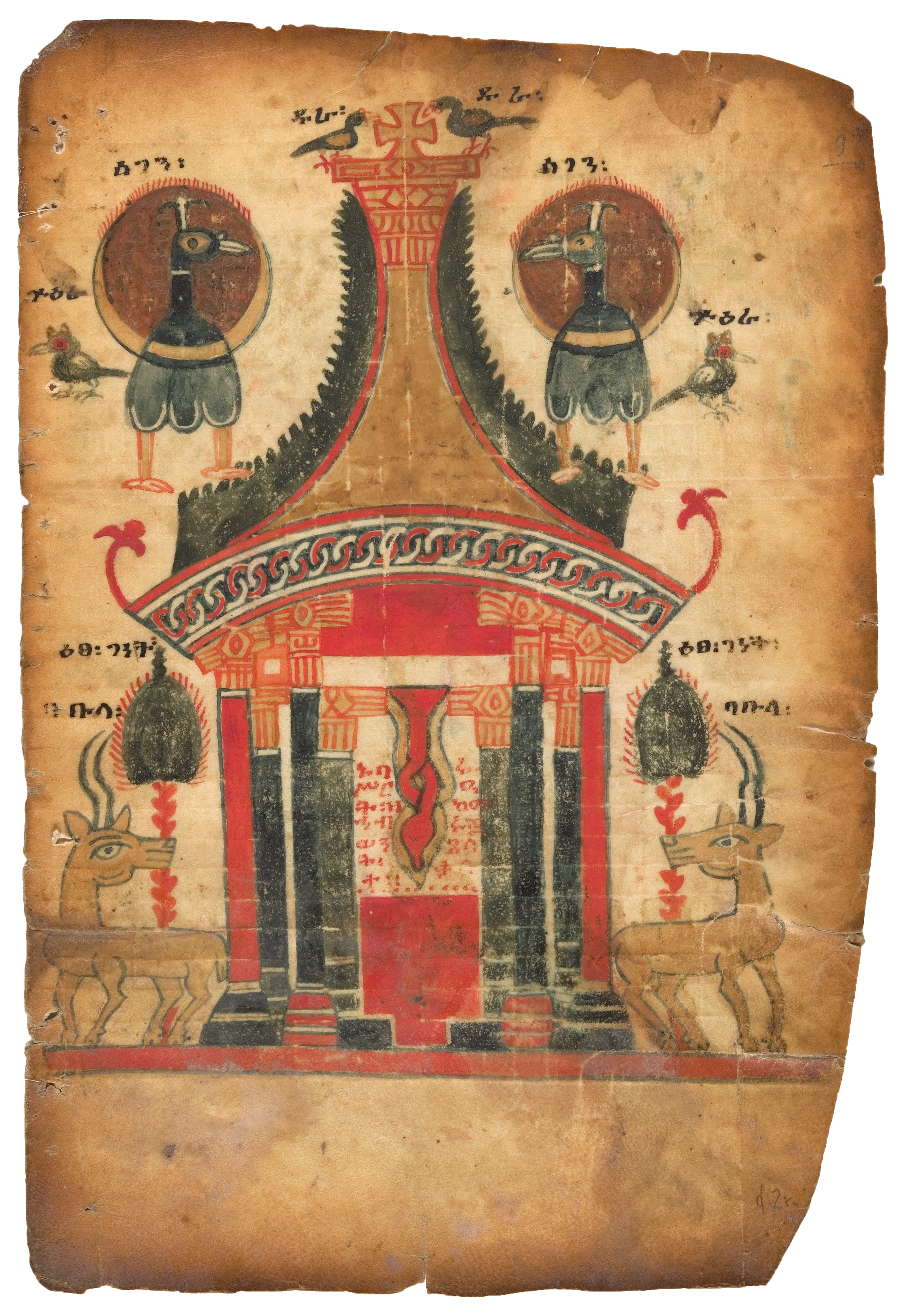

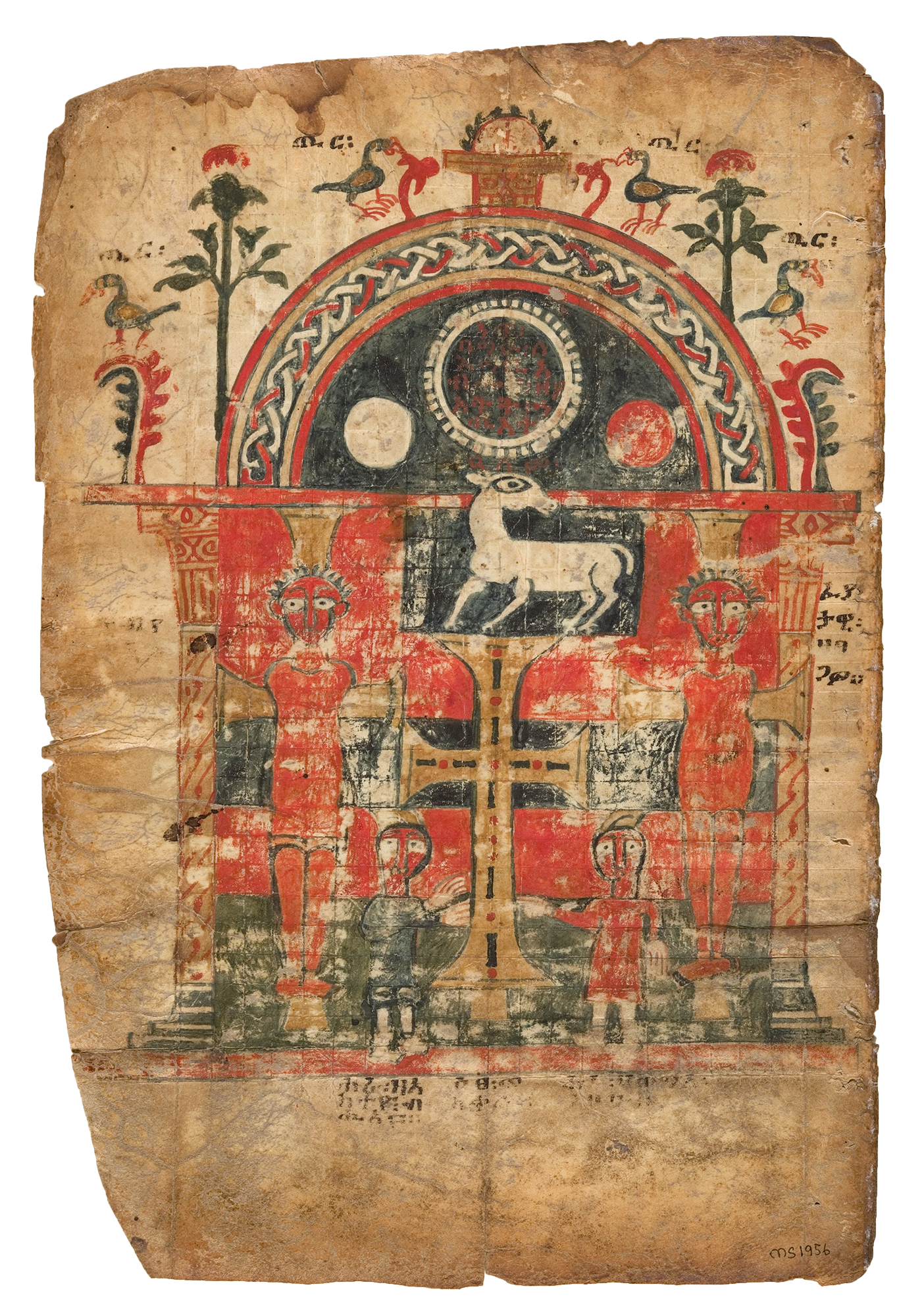

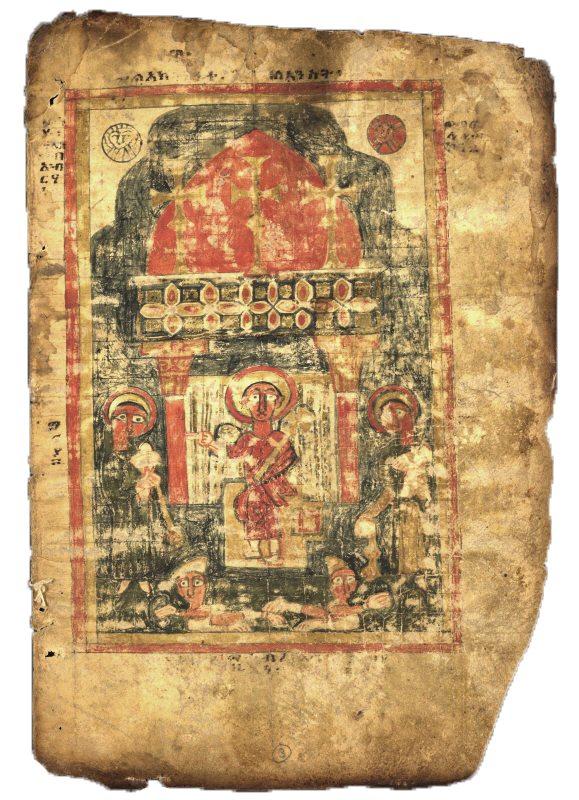

The “Eusebian apparatus” mentioned earlier—Eusebius’ letter, canon tables, and tholos—was followed by another regular set of page types: the “crucifixion without the crucified”, which depicts Jesus as literally a lamb of god; the women at the tomb; and the ascension, also sometimes termed “Christ in Majesty”.

Below, you can compare these four different page types across three different manuscripts.

tholos

crucifixion without the crucified

women at the tomb

ascension

BnF Eth 32—13th century [ms]

Walters W.836—early 14th century [ms]

These pages types may have been developed in Palestine in the earliest days of the church, and the “crucifixion without the crucified” in particular eventually faded from Christian art.

Fundamentally, this repetition—almost to the point of regularity—tell us what was deemed important enough to keep even as the gospel books evolved.

more context on Ethiopian gospel books and their iconography

Bausi, Alessandro, Reudenbach, Bruno and Wimmer, Hanna. Canones: The Art of Harmony: The Canon Tables of the Four Gospels. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110625844

Ethiopian Gospel Book—Getty Conversations, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ub1VLSFPEQs.

Gnisci, Jacopo. “The Dead Christ on the Cross in Ethiopian Art: Notes on the Iconography of the Crucifixion in Twelfth- to Fifteenth-Century Ethiopia.” Studies in Iconography 35 (2014): 187–228.

Gnisci, Jacopo. “Towards a Comparative Framework for Research on the Long Cycle in Ethiopic Gospels: Some Preliminary Observations.” Aethiopica 20, no. 1 (July 28, 2017): 70–105. https://doi.org/10.15460/aethiopica.20.1.972.

Gnisci, Jacopo, and Massimo Villa. “Evidence for the History of Early Solomonic Ethiopia from Tämben: Part II: Yoḥanni Däbrä ʿAśa.” Rassegna Di Studi Etiopici, January 1, 2022. https://www.academia.edu/46016158/Evidence_for_the_History_of_Early_Solomonic_Ethiopia_from_T%C3%A4mben_Part_II_Yo%E1%B8%A5anni_D%C3%A4br%C3%A4_%CA%BFA%C5%9Ba.

Gnisci, Jacopo, and Rafal Zarzeczny. “’They Came with Their Troops Following a Star from the East’; : A Codicological and Iconographic Study of an Illuminated Ethiopic Gospel Book,” OCP 83/1 (2017), Pp. 127-189. https://www.academia.edu/34500071/_They_Came_with_their_Troops_Following_a_Star_from_the_East_A_Codicological_and_Iconographic_Study_of_an_Illuminated_Ethiopic_Gospel_Book_OCP_83_1_2017_pp_127_189.

Heldman, Marylin E. and Devens, Monica S.. 2005. “The four Gospels of Däbrä Mäar: colophon and note of donation”, Scrinium, 1, 77–99.

https://www.academia.edu/59061901/THE_FOUR_GOSPELS_OF_D%C3%84BR%C3%84_M%C3%84cAR_COLOPHON_AND_NOTE_OF_DONATION.

14th–15th century

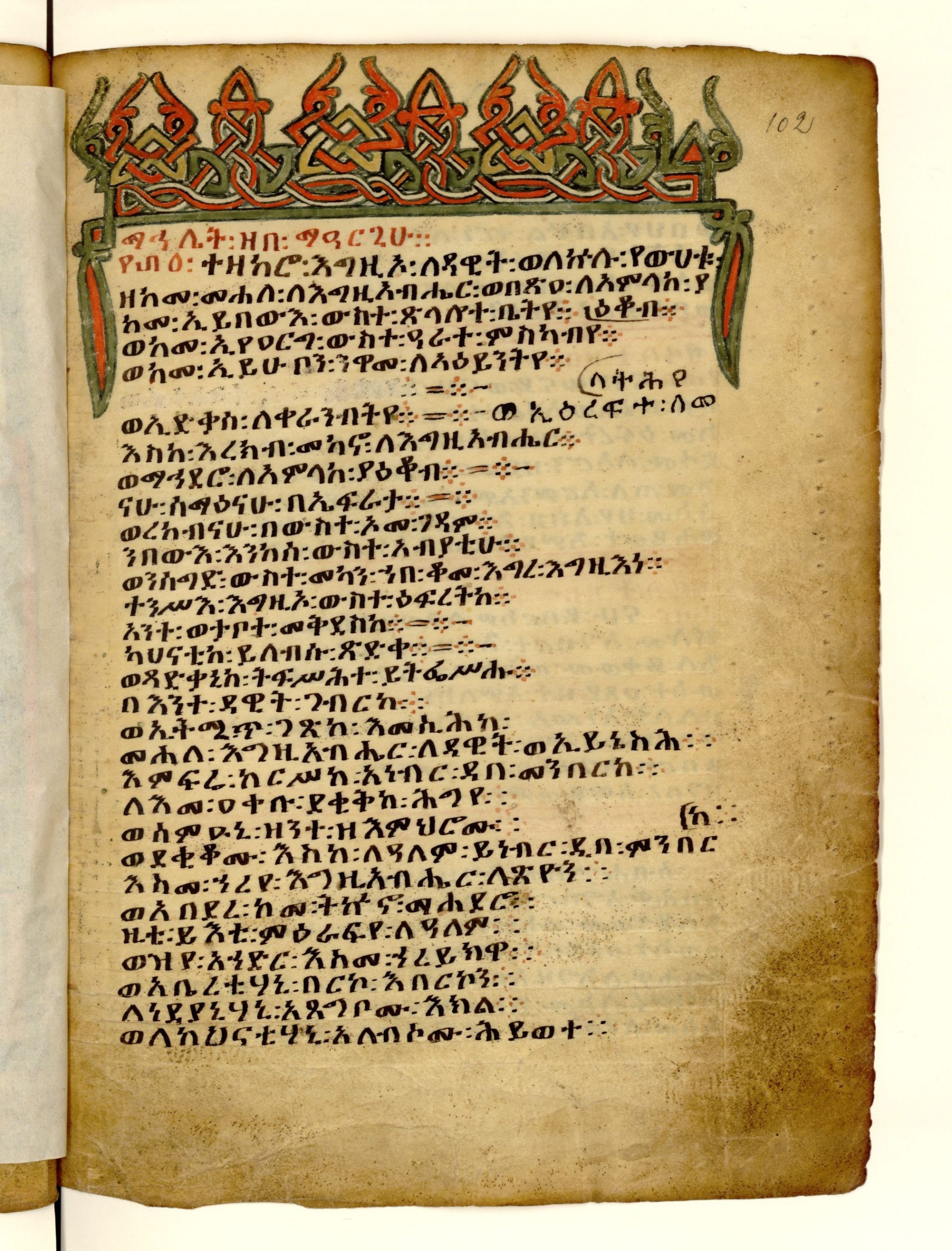

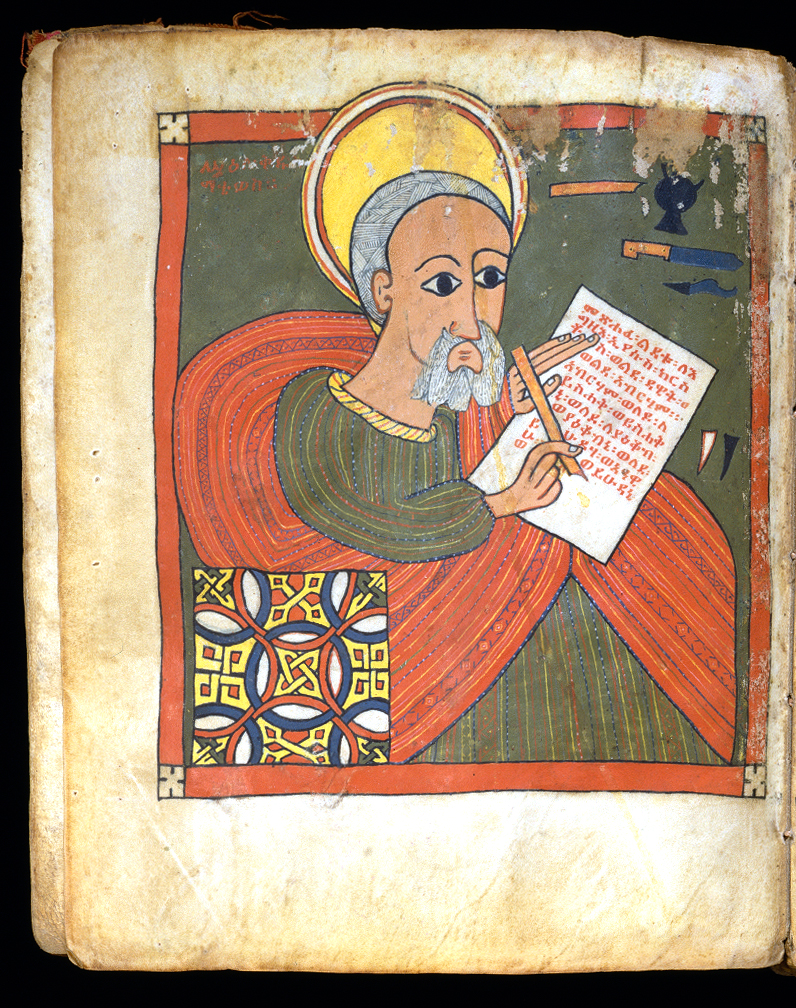

The extant art of the fourteenth century begins predominately with gospel books, but eventually diversifies to include octateuch (a manuscript consisting of the first eight books of The Old Testament), as well as psalters like this one:

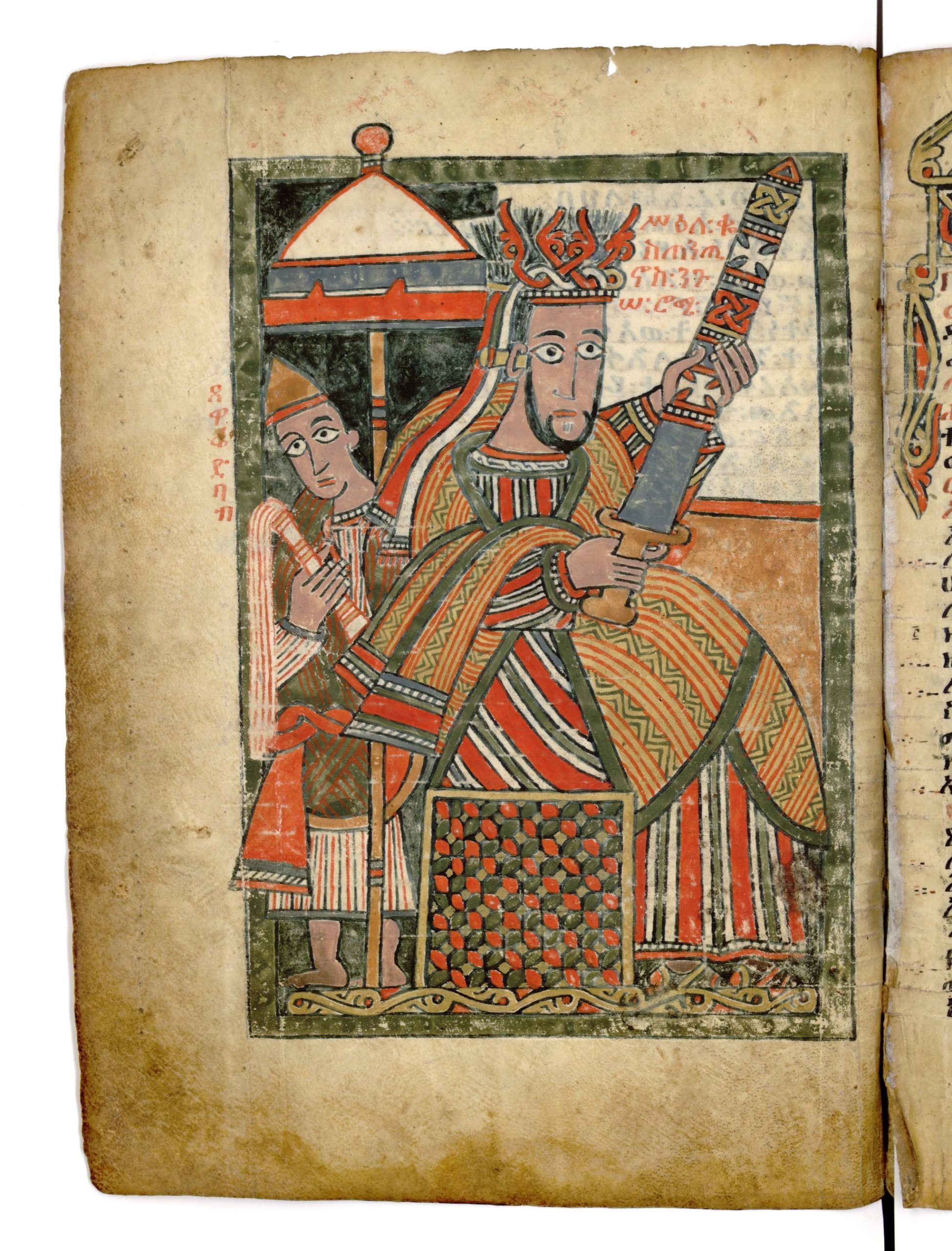

This is BnF ms. Abb. eth. 105, sometimes called “Belen Saggad’s Psalter” for the man who commissioned it. (His portrait is on folio 89v.) It’s a good example of the Ewostatewosite style, an illumination style developed at monastaries established by disciples of Ewostatewos. This manuscript was created in 1476/7 and contains many full-page illuminations, including portraits of Constantine (a highly-respected leader), the Biblical David (who wrote the psalms contained in the psalter), Mary and Child, and more.

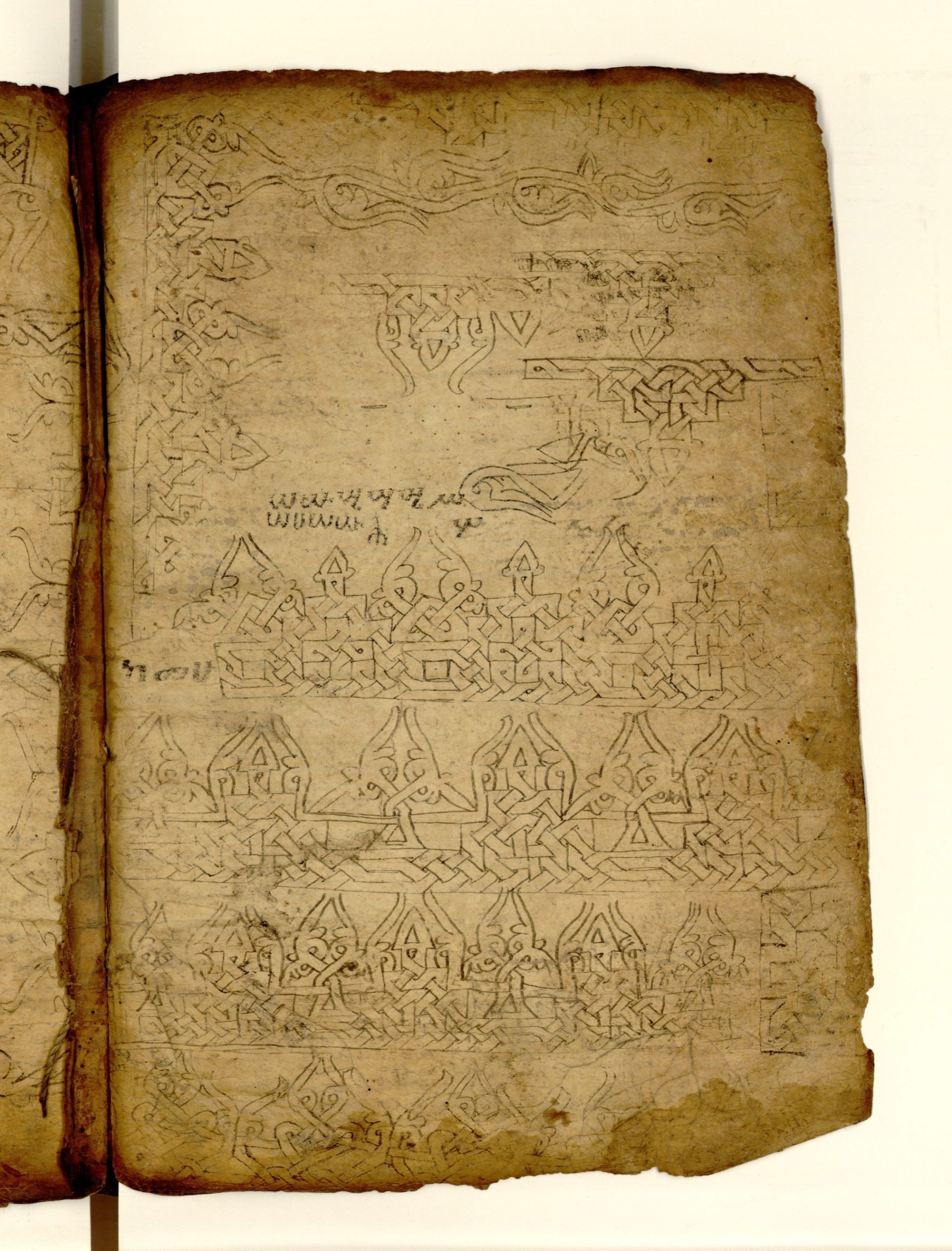

The manuscript contains many headpieces like the one at left, an early example of the Ethiopian haräg. Haräg is the Ge’ez word for the tendril of a climbing plant, a poetic term for the element.

Conventionally, no two haräg are repeated within a manuscript, which provides for the illuminator an opportunity of creativity within a proscribed framework. Haräg were rare and scattered before this period, after which point they began to very quickly increase in frequency and become more involved.

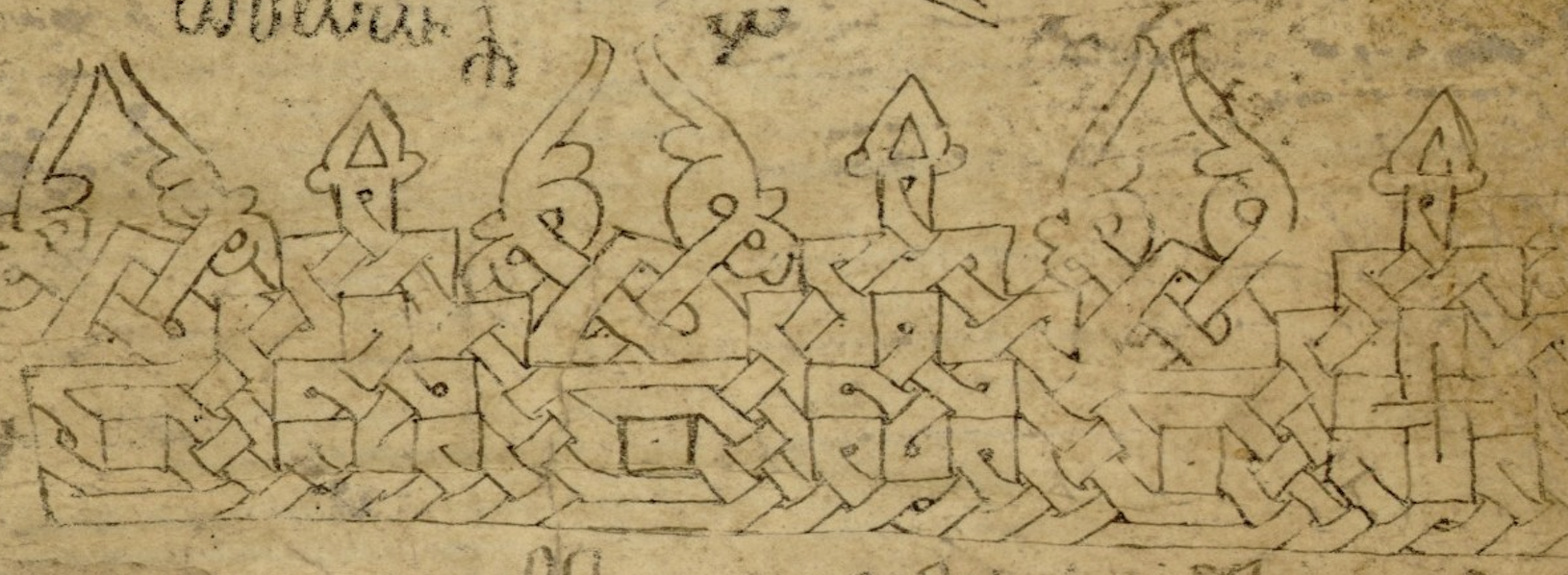

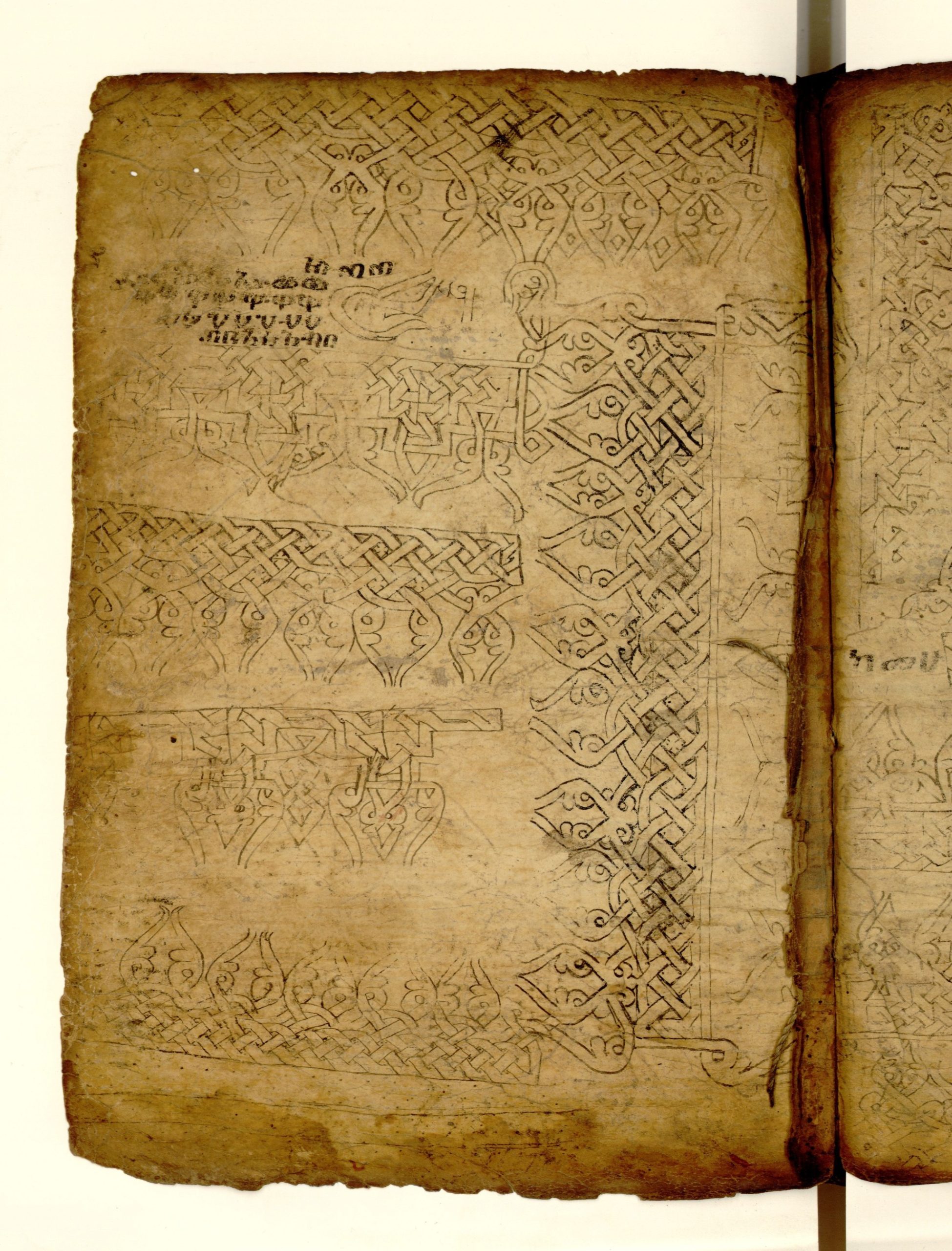

BnF ms. Abb. eth. 105 is also useful for artists due to a few pages filled with ornaments which appear to be neither pen trials nor unfinished, but full pages of ornament and interlace sketchwork. At right, please enjoy the triangular terminals, as well as those formed by Dr Suess-like half palmette hands, and the relatively tight grid onto which the interlace is mapped. Looking at the artist’s plans without color can help us in our own constructions.

15th–early 16th century

ICONS

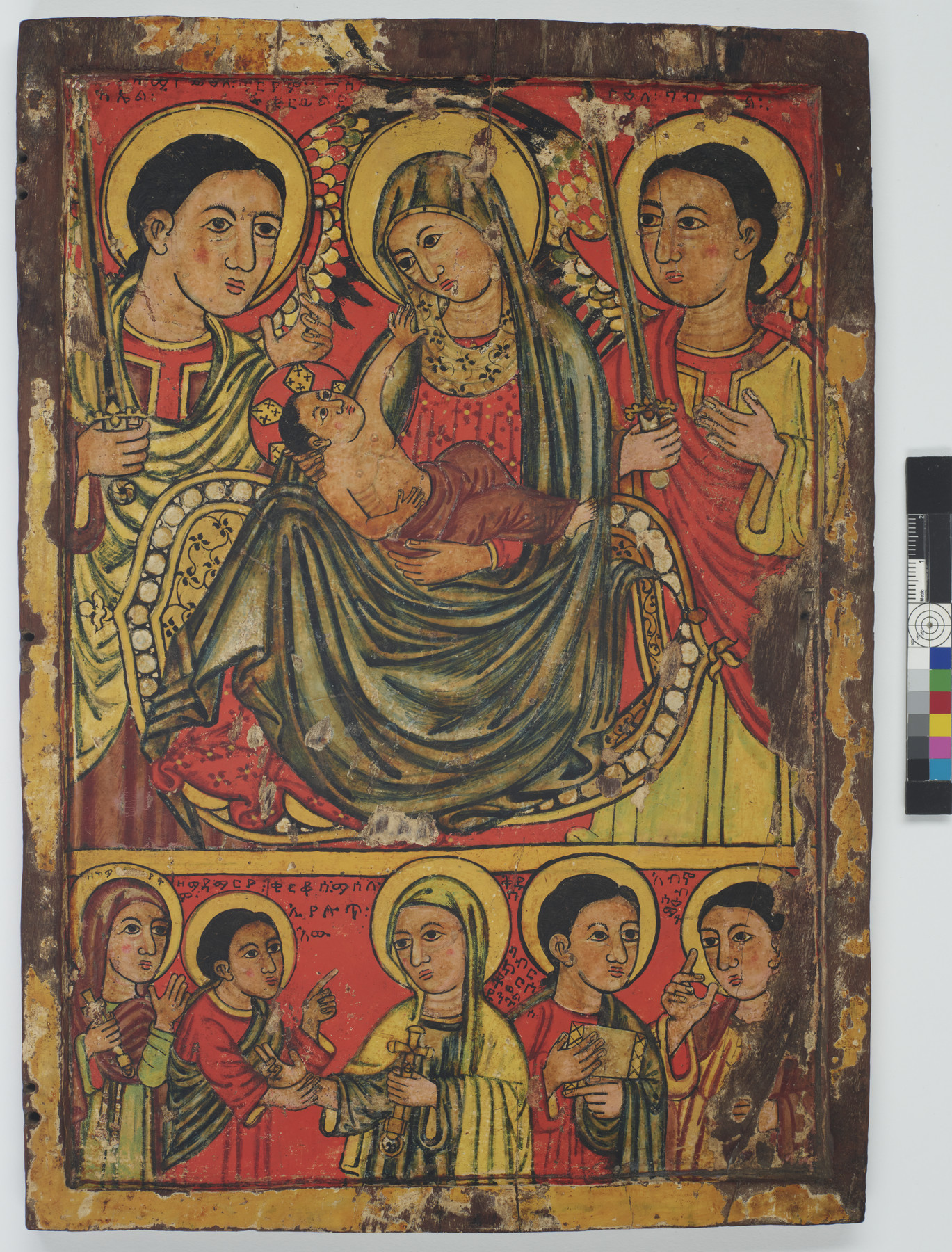

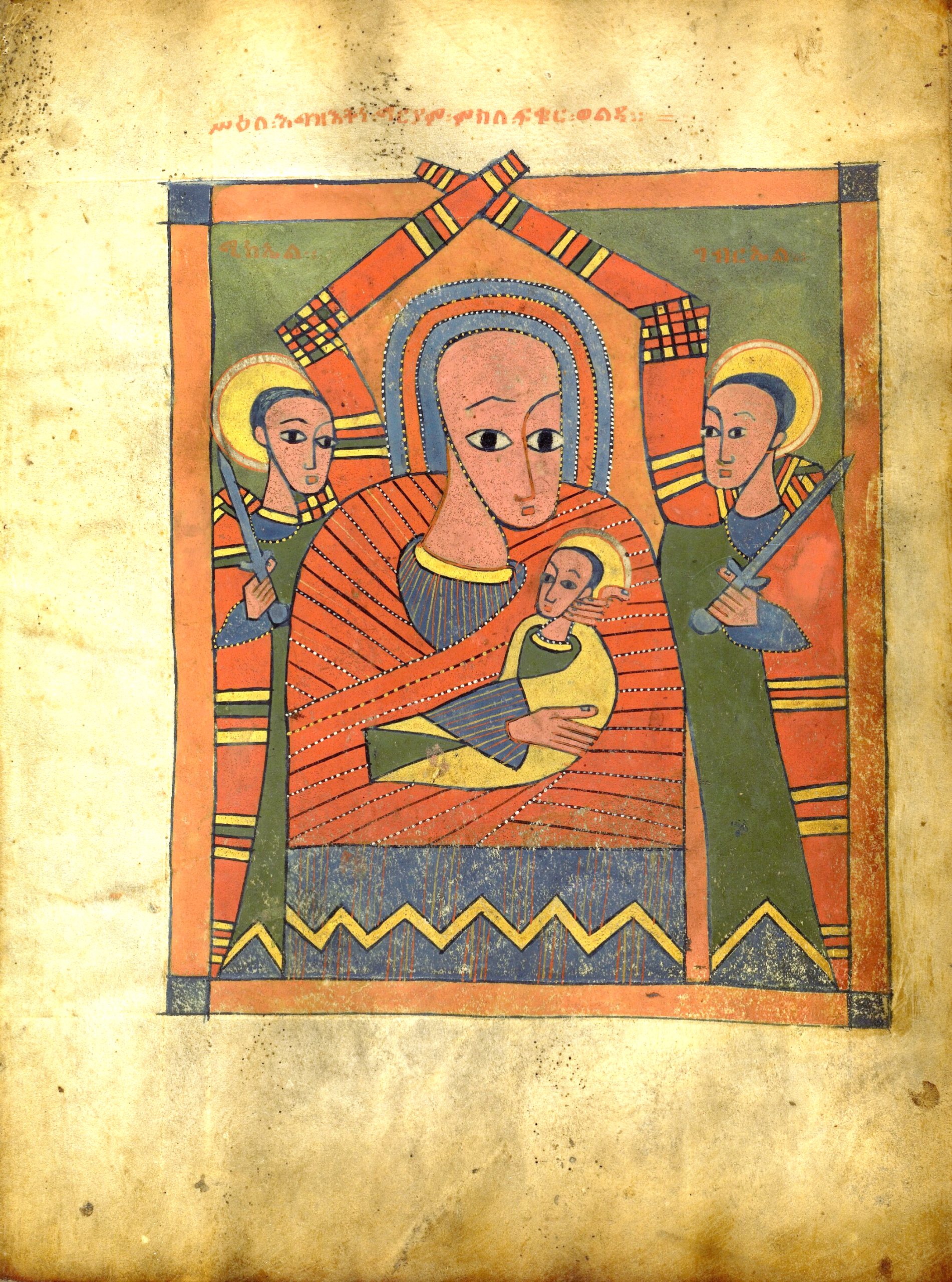

In 1441 Emperor Zara Yaqob established a mandatory ritual veneration of Mary, placing her central to salvation as an intercessor between the pray-er and her son. As part of this, he encouraged and sponsored production of Mary-centered icons and iconography. As such, it’s at this point that we see a shift of frequency and manner in the portrayal of Mary and child. And nowhere is this more in evidence than in the proliferation of icons featuring the two.

Icons are items of veneration, and can take the form of anything that can carry an image: paintings and objects are popular forms. Once again, the Gə’əz word “sə’əl” means both 2D and 3D image, therefore sidestepping the iconoclastic troubles of other forms of Christianity.

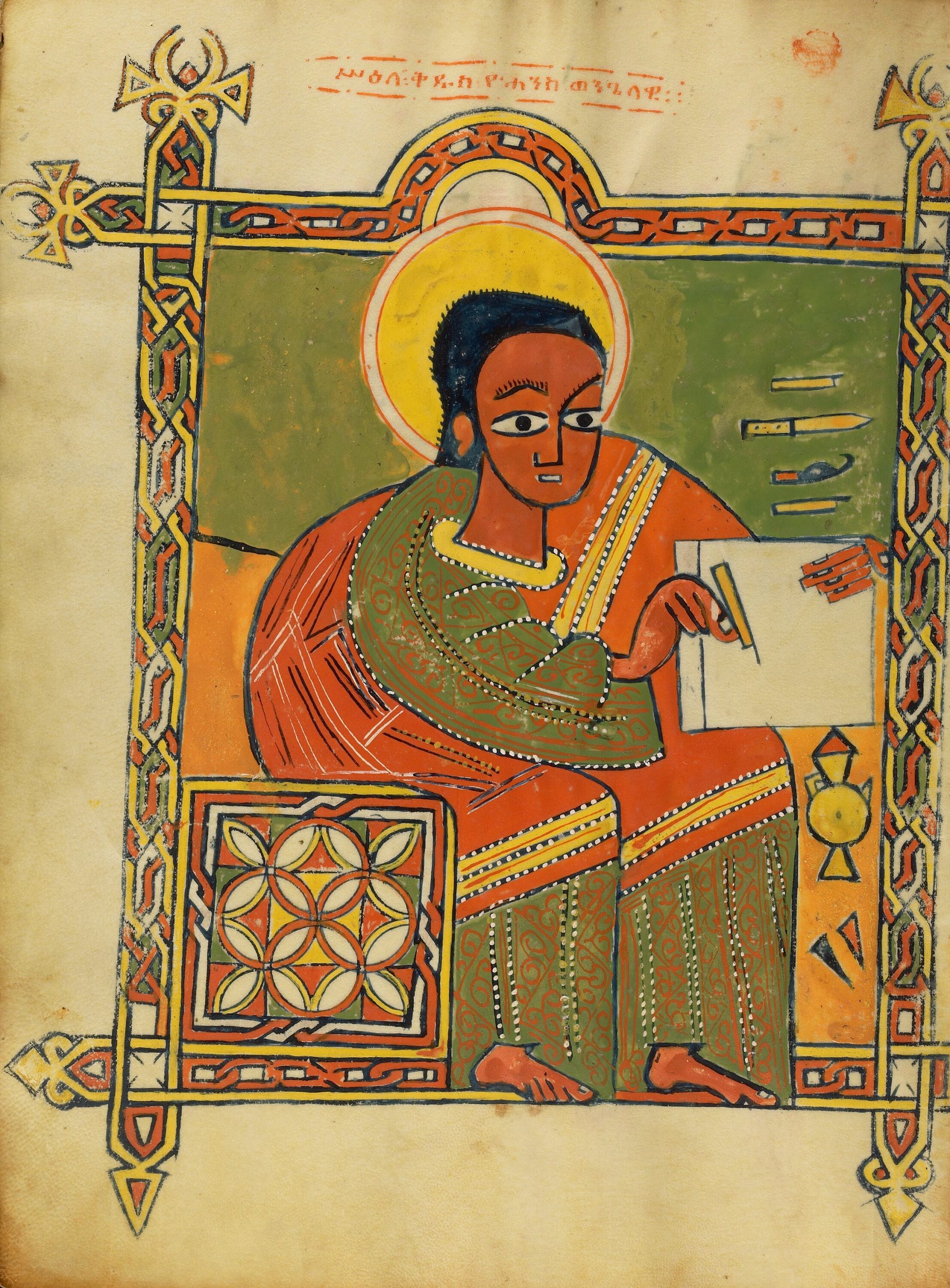

There are few named painters from this period—it was considered a lack of Christian humility for artists to sign their work—but one such painter is named Fre Sayon, an influential court painter. His single signature among a handful of paintings attributed to him may be an indication of influence from Europe, as is his posing of the figures with Jesus touching his mother’s face.

While only a few are said to be his work, many more extant icons are attributed to followers of his “school” of painting style, like the example above at left. At right, the figures’ rounded faces and sweeping draperies also recall his style: a sign of his impact.

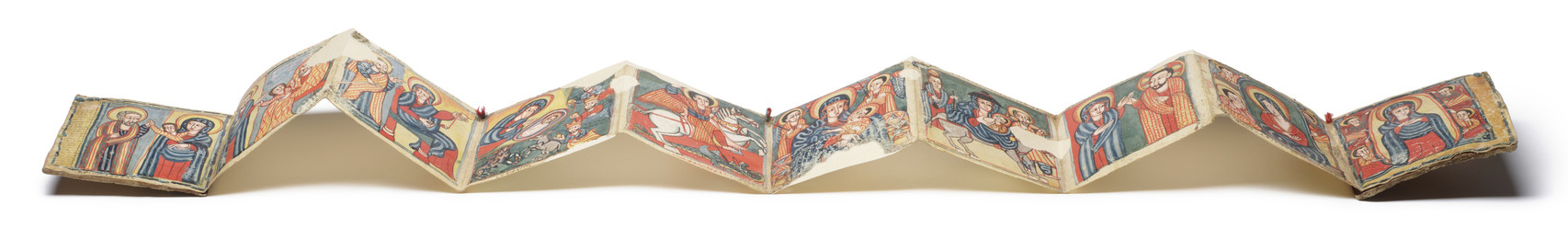

Folded icons were also an important form. The sensul— a particularly Ethiopian object made from one or more sheets of parchment attached together, folded accordion-style, and sandwiched between boards of wood or hide, in effect a hybrid between an illuminated manuscript and a painted icon on wood—is one such form. It first appeared in 15th century Ethiopia, gradually faded in popularity, and flourished again in the 17th.

The leaf at left is from a dispersed 15th century sensul, three leaves of which are held at the Walters. When fully assembled, the figures create a parade which conveys a sense of linear movement. It’s palm-sized, indicating that it was created for personal use. Sensuls often lack text apart from basic inscriptions, and while most only carry illustrations on one side of the parchment, this one has images on both, doubling the number of diptych-like turns of the page which could be venerated.

Linear movement is a feature which arises often in Ethiopian Christianity through multiple forms: the sensul, ceremonial procession, the vertical procession of figures in a Ethiopian prayer scroll, the multiple registers of figures in frontispiece illustrations of some Gospel books and painted icons (such as the ones above), and liturgical fans.

The 15th century liturgical fan above and at left comes from church of Debre Tsion (Abuna Abreham). Many of the larger churches in Ethiopia had such fans, though only a few remain extant. The fans themselves could be carried in procession, but procession is also conveyed by the parade of figures around the fan—especially when they were in motion as a fan was folded and unfolded.

The image below is a similar object, un-fanned, held at the Walters Art Museum.

some resources on Ethiopian icons

Bosc-Tiessé, Claire. “Sə’əl. Spirit and Materials of Ethiopian Icons,” December 1, 2009. https://www.academia.edu/1770685/Seel_Spirit_and_Materials_of_Ethiopian_Icons.

“Ethiopian Icons: Faith & Science || National Museum of African Art.” https://africa.si.edu/exhibits/icons/index.html.

Heldman, Marilyn E. “Frē Seyon: A Fifteenth-Century Ethiopian Painter.” African Arts 31, no. 4 (1998): 48–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/3337648.

Sciacca, Christine. “A ‘Painted Litany’: Three Ethiopian Sensul Leaves from Gunda Gunde.” The Journal of the Walters Art Museum 73 (2018): 92–95. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26537584.

Sciacca, Christine. “Exploring Sensuls: An Indigenous Manuscript Tradition in Ethiopia.” Text, March 7, 2023. https://journal.thewalters.org/volume/76/essay/exploring-sensuls-an-indigenous-manuscript-tradition-in-ethiopia/.

GUNDA GUNDË

Previous to this, we had chiefly been speaking in terms of time period rather than style. But there is one style name which comes up frequently, and is generally accepted as a term.

The Gunda Gundë style is known for features like flat colour, geometric shape, extreme stylization, the eye shape, rounded outlines of figures, and a dotted motif in the clothing. The style developed in the Ǝsṭifanosite or Stephanite monasteries, a simplification of the Ewosṭatean style mentioned above.

The manuscripts above are all gospel books, but the style is represented widely, including the processional icon (horizontally-opened fan) above, Walters 36.9. In the detail at left, you can see a particularly strong relationship with the gospel book directly above, Walters W.850.

resources about the relationship between textiles and Ethiopian mss

Eyob Derillo, Michael Gervers, “The Textiles in Manuscripts Workshop”, Institute for Advanced Study, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pMyF79yubW8.

“Textiles in Ethiopian Manuscripts at the British Library.” https://blogs.bl.uk/collectioncare/2021/12/textiles-in-ethiopian-manuscripts-at-the-british-library.html.